Introduction

If you work with thyroid cases regularly, you have almost certainly encountered patients who challenge the simplicity of conventional endocrine interpretation. They present with unmistakable thyroid symptoms such as persistent fatigue that does not resolve with rest, unexplained weight shifts, hair thinning, mood dysregulation, cold intolerance, menstrual irregularities, reduced exercise tolerance, and cognitive slowing. Yet their laboratory report states what many clinicians are trained to consider reassuring: everything is normal.

TSH falls within reference range.

Hormone levels appear adequate.

No further action required.

But the patient is clearly not functioning normally.

This disconnect is not rare, rather it is a routine. And it reveals something important about how thyroid physiology is taught and interpreted in most clinical settings. Conventional training often emphasizes diagnostic thresholds for overt thyroid disease but does not sufficiently prepare practitioners to interpret regulatory dysfunction that exists before or outside those thresholds. In other words, clinicians are trained to identify gland failure, but not to analyze hormone signaling across systems.

This difference is subtle, yet profoundly important.

Because thyroid regulation is not determined only by how much hormone the gland produces. It is shaped by transport proteins, conversion enzymes, immune surveillance, mitochondrial activity, autonomic nervous system tone, inflammatory signaling, and cellular receptor sensitivity. Hormone availability is only one variable in a much larger regulatory network.

When patients present with persistent symptoms despite normal thyroid levels, the issue is rarely measurement error. More often, it is an interpretive limitation. The numbers are being read correctly but understood incompletely.

Clinical thyroid interpretation, therefore, must move beyond identifying hormone presence. It must evaluate hormone behavior.

That shift, right from measurement to interpretation is where advanced practice begins.

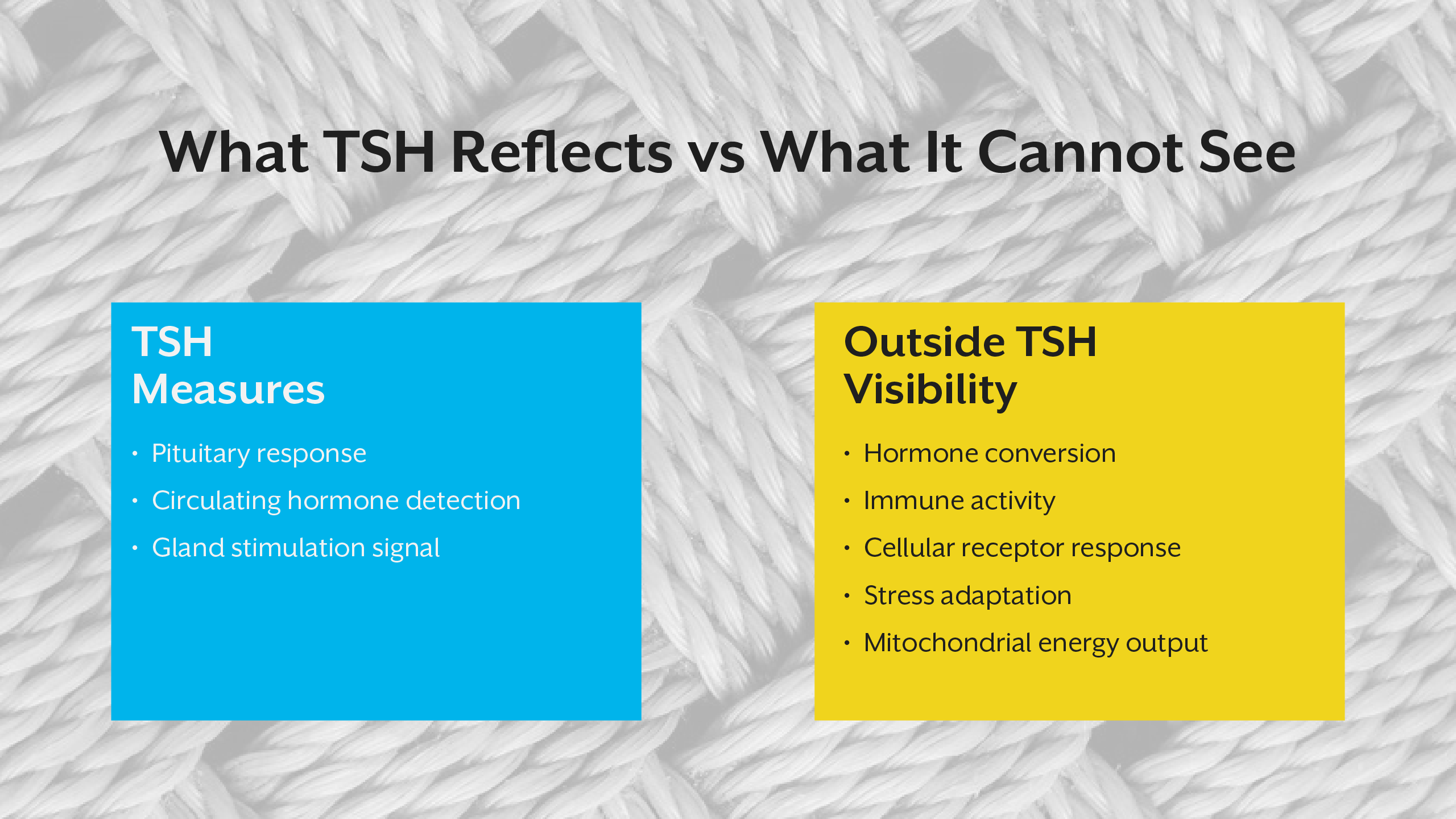

What TSH Actually Measures (And What It Does Not)

Thyroid-stimulating hormone is widely treated as the central indicator of thyroid function. Yet physiologically, TSH reflects something quite specific: the pituitary gland’s perception of circulating thyroid hormone levels.

It does not directly measure tissue activity. It does not quantify cellular energy production. It does not indicate receptor sensitivity. And it does not reveal how effectively hormones are converted into their active form.

TSH is a regulatory signal within a feedback loop - nothing more, nothing less.

The pituitary monitors circulating thyroid hormones and adjusts TSH output accordingly. When hormones appear low, TSH rises to stimulate more production. When hormones appear sufficient, TSH decreases. This mechanism maintains systemic stability, but it does not guarantee uniform tissue response.

Different organs respond to thyroid hormone differently. Conversion rates vary by tissue. Local metabolic demands shift dynamically. Stress hormones, inflammatory mediators, and nutrient availability all influence how thyroid hormone is used at the cellular level. None of this complexity is captured by TSH.

This is why patients can display significant functional hypothyroidism at the tissue level even while circulating hormones appear adequate. The pituitary may detect enough hormone in the bloodstream, yet individual cells may not receive, convert, or respond to it effectively.

Interpreting TSH as a comprehensive indicator of thyroid health therefore oversimplifies endocrine physiology. It is a useful marker, but it is not a complete one. Treating it as definitive creates blind spots in clinical reasoning.

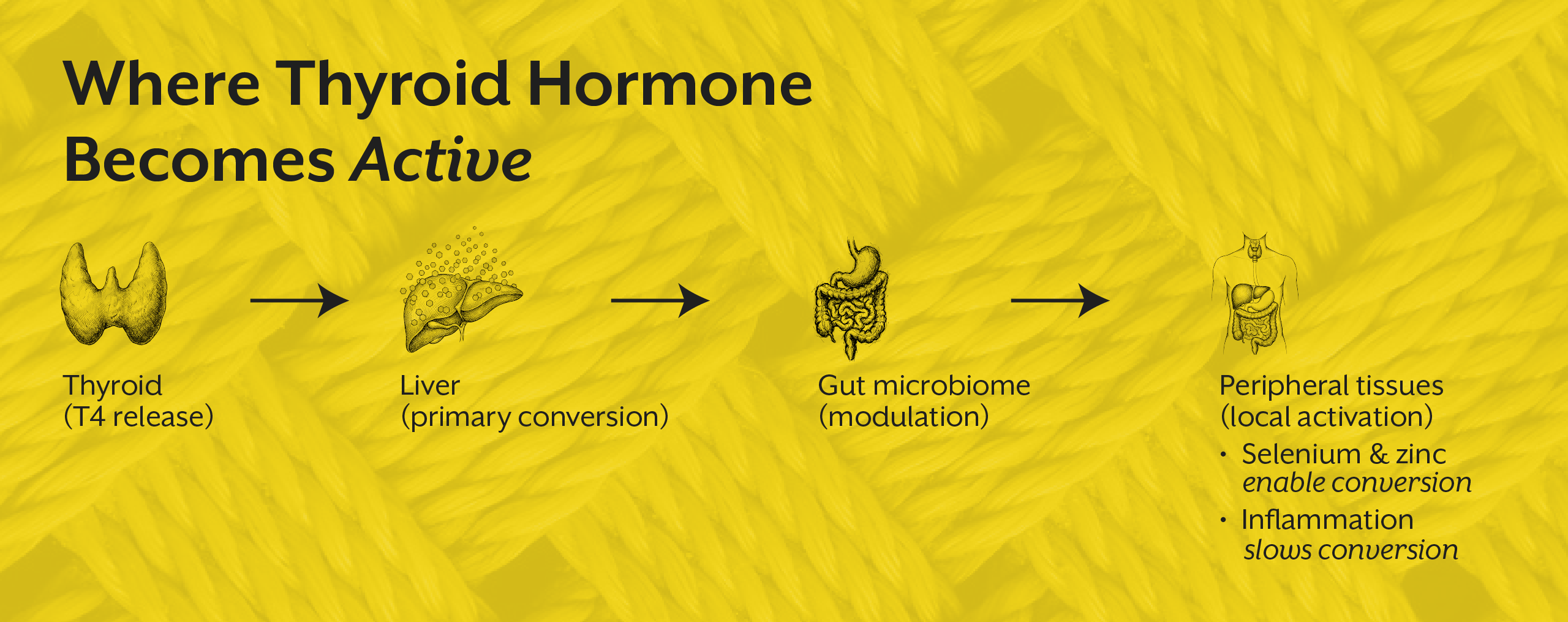

The Thyroid Hormone Cascade: From Production to Cellular Action

To understand why lab interpretation requires nuance, it helps to examine how thyroid hormone actually functions biologically.

The process unfolds in stages. First, the thyroid gland produces primarily thyroxine (T4), a relatively inactive hormone designed largely for transport. This hormone circulates through the bloodstream, bound to carrier proteins, until it reaches tissues capable of activating it. Through enzymatic conversion, T4 is transformed into triiodothyronine (T3), the metabolically active form that interacts with cellular receptors to regulate gene expression and energy production.

This means the majority of thyroid hormone activation happens outside the thyroid gland itself. Liver tissue plays a major role, as does the gastrointestinal environment, where microbial activity influences conversion dynamics. Peripheral tissues also generate local activation according to metabolic demand.

If conversion is impaired due to factors involving inflammation, nutrient deficiency, liver dysfunction, chronic stress, or illness circulating hormone may remain plentiful while active hormone becomes insufficient. Laboratory panels that measure only production cannot capture this bottleneck.

This is one of the most common reasons thyroid treatment appears ineffective. Hormone is supplied, yet activation remains compromised. From a biochemical standpoint, the body is not lacking hormones, in fact it is lacking a usable signal.

Understanding this cascade shifts clinical focus from gland output alone to metabolic context. Hormone production is the beginning of thyroid physiology, not its endpoint.

Thyroid Antibodies and the Timeline of Autoimmune Activity

Another critical layer of interpretation involves immune system behavior. Thyroid autoimmunity often develops gradually, sometimes years before measurable hormone disruption occurs. During this period, patients may experience fluctuating symptoms while standard hormone tests remain within range.

Thyroid antibodies provide early insight into this process. They reveal immune recognition of thyroid tissue as a target, which is an event that may precede structural damage and functional decline.

When antibody activity is present, the clinical question is no longer whether thyroid function is currently impaired, but whether it is likely to become impaired over time. Antibodies describe trajectory. They indicate that regulatory stability is being challenged, even if laboratory hormone levels have not yet shifted significantly.

This distinction is especially relevant in autoimmune thyroiditis, where inflammatory processes gradually alter gland architecture. Waiting for hormone levels to deteriorate before acknowledging dysfunction is analogous to recognizing metabolic disease only after organ failure has begun.

From a preventive and functional perspective, antibody detection provides an opportunity to intervene earlier in the disease continuum before irreversible tissue loss occurs.

Reverse T3 and the Physiology of Metabolic Adaptation

One of the most clinically revealing yet frequently misunderstood thyroid markers is reverse T3. Rather than representing simple hormonal inactivity, reverse T3 reflects a strategic metabolic adjustment.

Under conditions of physiological stress like infection, inflammation, caloric restriction, trauma, or chronic psychological strain, the body modifies hormone conversion patterns. Instead of generating metabolically stimulating T3, it increases production of reverse T3, which dampens metabolic intensity.

This shift conserves energy, reduces oxidative demand, and supports survival during perceived threat.

Importantly, this mechanism is not pathological by design. It is adaptive. However, when stress becomes chronic, this adaptive shift can become prolonged, leading to persistent symptoms of low metabolic activity despite normal thyroid production.

Patients in this state often exhibit adequate T4 levels, reduced T3 availability, and elevated reverse T3. Without contextual interpretation, this pattern may be mistaken for gland dysfunction when it actually reflects systemic stress physiology.

Reverse T3 therefore provides insight into metabolic prioritization. It reveals how the body is allocating energy under pressure.

Cellular Responsiveness and Thyroid Hormone Resistance

Even when hormone production and conversion appear sufficient, thyroid function can remain impaired if cellular responsiveness is reduced. This phenomenon is often described as functional hormone resistance.

At the cellular level, thyroid hormone binds to receptors that influence gene transcription, mitochondrial activity, and metabolic output. If receptor signaling is disrupted by inflammatory mediators, oxidative stress, insulin resistance, or impaired mitochondrial function, hormone presence does not translate into biological effect.

In this scenario, laboratory hormone levels may appear optimal while tissue function remains diminished.

Clinically, this explains why some patients do not improve despite hormone replacement or normalization of circulating markers. The issue is not hormone availability but signal reception.

Understanding thyroid physiology therefore requires attention to the intracellular environment, not just endocrine output.

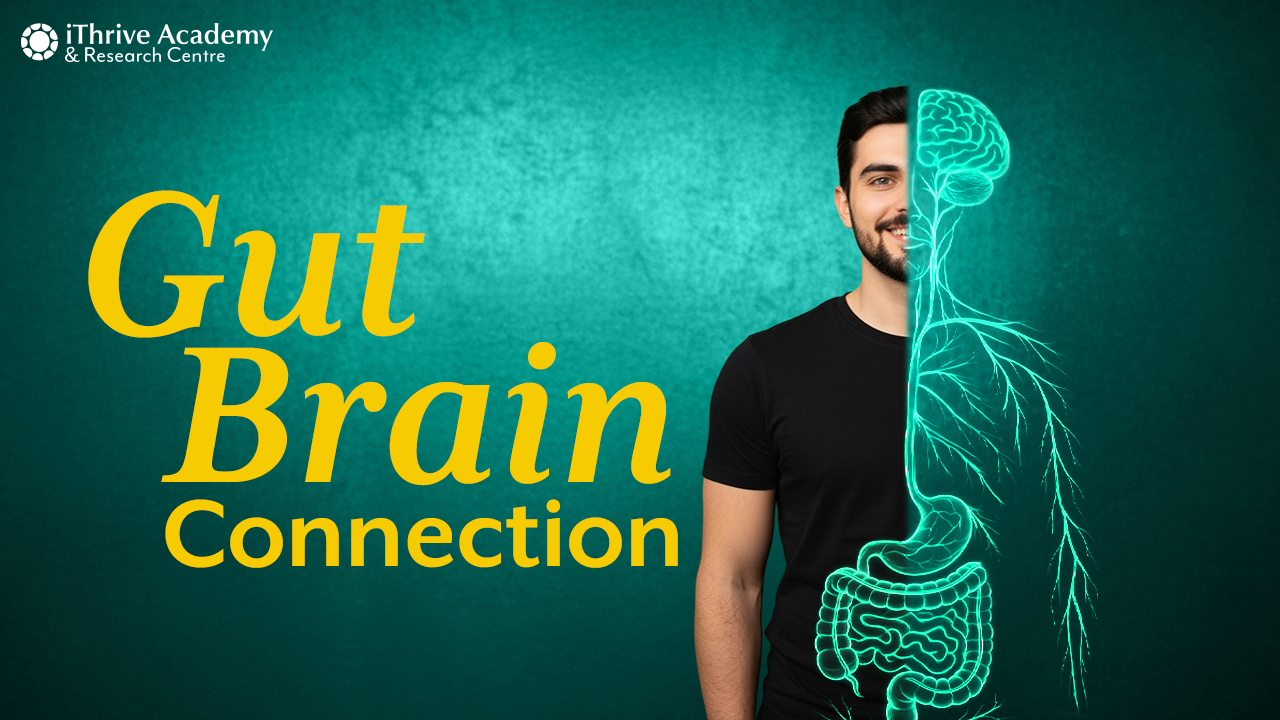

Nervous System Regulation and Thyroid Signaling

The thyroid operates within an integrated neuroendocrine network. Autonomic nervous system activity influences metabolic demand, hormone conversion patterns, and receptor sensitivity.

Sympathetic dominance that is commonly associated with chronic stress can alter peripheral conversion, shift energy allocation, and modify cellular responsiveness. Parasympathetic insufficiency can impair digestion, nutrient assimilation, and restorative processes that support endocrine balance.

These neural influences help explain why thyroid symptoms often fluctuate with psychological stress, sleep disruption, and life events. Hormone concentration may remain stable, yet physiological experience changes because regulatory signaling has shifted.

This neuroendocrine integration highlights why thyroid interpretation cannot be separated from stress physiology. Hormone behavior reflects the broader regulatory environment in which it operates.

A patient has normal TSH, low free T3, elevated reverse T3, and chronic fatigue.

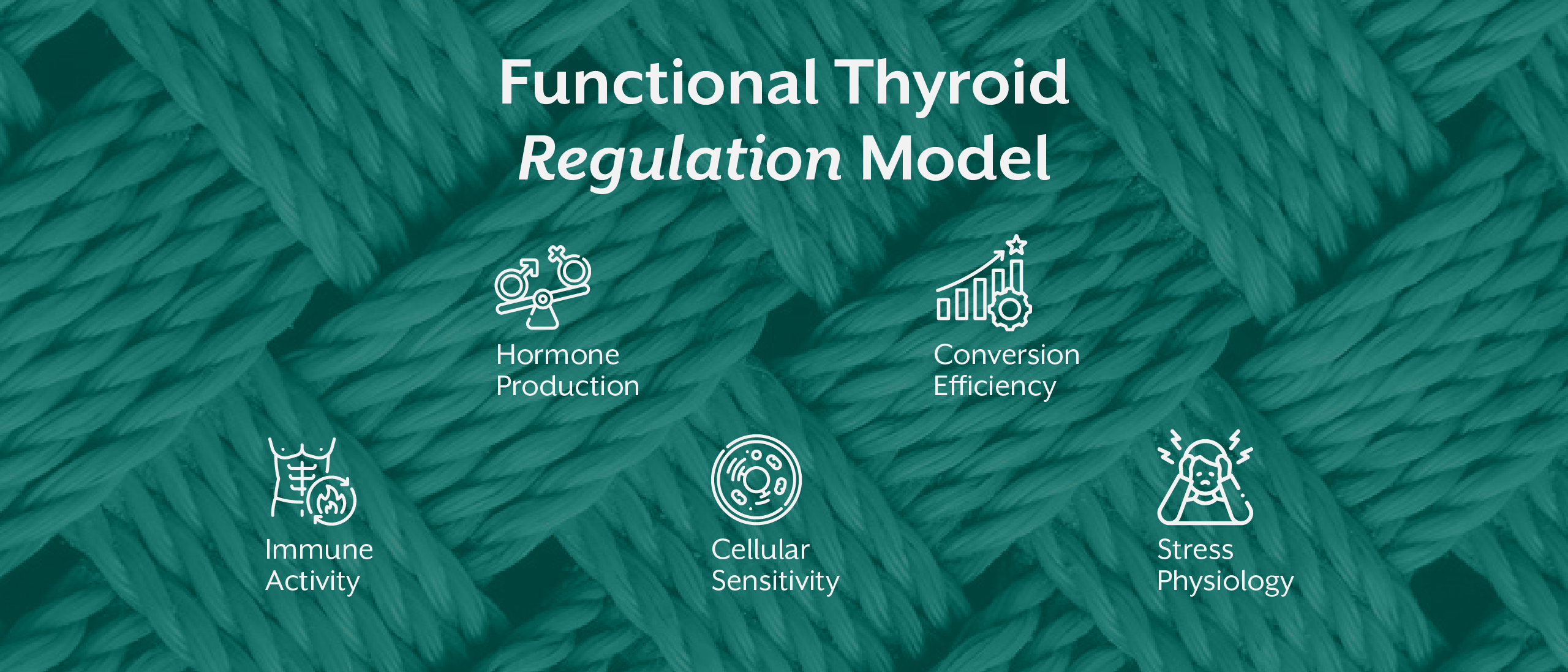

Integrating Thyroid Markers Into a Systems-Level Clinical Model

Meaningful thyroid assessment requires synthesis of multiple physiological dimensions. No single marker can capture endocrine performance across tissues, metabolic states, immune activity, and neural regulation.

Comprehensive interpretation involves examining hormone production, activation, immune surveillance, stress adaptation, and cellular responsiveness simultaneously. Each domain informs the others. Patterns emerge only when markers are considered collectively rather than in isolation.

This systems-level approach transforms thyroid care from reactive diagnosis to functional understanding. Instead of asking whether hormone levels are abnormal, the clinician asks how regulatory networks are interacting and why symptoms persist despite apparent biochemical stability.

Training that emphasizes this interpretive depth enables practitioners to move beyond surface measurements and engage with the dynamic physiology that underlies thyroid function.

Key Takeaway

Interpreting thyroid laboratory markers beyond TSH requires a shift from numeric evaluation to physiological reasoning. Thyroid hormone activity is not determined solely by gland production but by a cascade of regulatory processes involving conversion efficiency, immune signaling, stress adaptation, autonomic regulation, and cellular responsiveness. When clinicians recognize that laboratory values represent only fragments of a larger endocrine narrative, interpretation becomes more precise, treatment becomes more individualized, and patient outcomes become more predictable. Advanced thyroid assessment is not about identifying abnormal numbers, rather it is about understanding biological regulation in context.

.jpg)