Introduction

If you have studied nutrition formally, or if you teach it, you may have noticed something uncomfortable.

You learn nutrients.

You learn about food groups.

You learn calorie balance.

You learn disease management guidelines.

But you are rarely taught how metabolic disease actually develops inside the body over time.

This is the hidden gap in nutrition education.

Obesity is usually taught as a consequence of energy imbalance. Metabolic syndrome is presented as a cluster of risk factors. Insulin resistance is explained as impaired glucose handling. Each concept is technically correct, yet clinically incomplete.

Because in real patients, obesity causes are not isolated mechanisms. They are evolving physiological adaptations emerging from chronic metabolic stress across multiple systems simultaneously.

And most nutrition courses never teach you how to see that progression.

They teach outcomes.

They do not teach metabolic trajectory.

Understanding this distinction is essential if you want to truly understand the root cause of obesity, not just its visible manifestations.

Obesity Is Taught as a Static Condition - But Metabolic Disease Is Dynamic

One of the biggest conceptual limitations in traditional nutrition education is that obesity and metabolic disease are presented as fixed states.

A person “has obesity.

A patient “develops metabolic syndrome.

Someone “becomes insulin resistant.

But physiology does not work in static labels. It operates in continuous adaptation.

Long before weight gain becomes visible, metabolic flexibility begins to decline. Long before fasting glucose rises, insulin secretion patterns change. Long before diagnosis, tissues reorganize how they store, release, and utilize energy.

Metabolic disease is a timeline, not an event.

Yet most training models do not teach learners to map metabolic history. They focus on present-day measurements rather than long-term physiological shifts.

This creates a major clinical blind spot: intervention begins only after adaptation has become entrenched.

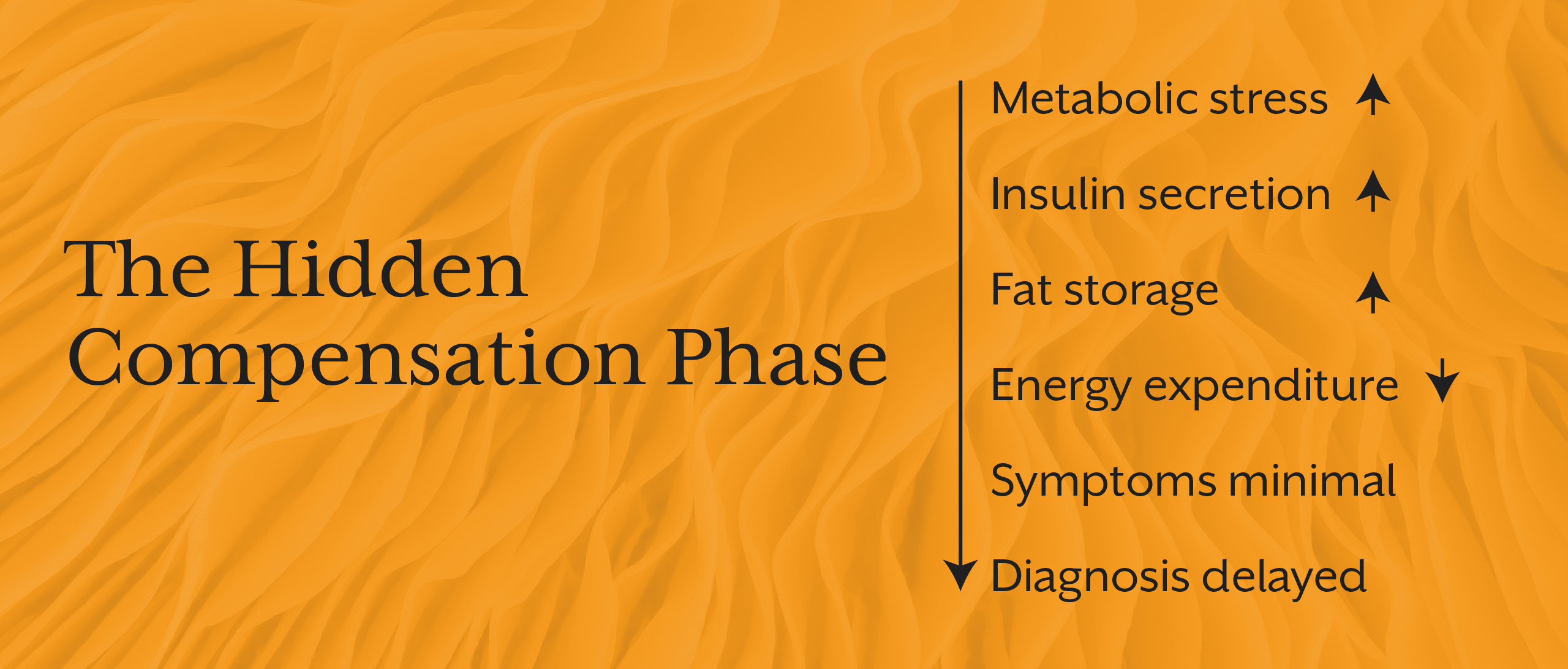

The Missing Concept: Metabolic Compensation

Perhaps the most overlooked concept in nutrition education is compensation.

The human body resists dysfunction for as long as possible. When metabolic strain rises, regulatory systems do not fail immediately, they adapt.

Examples include:

- Increased insulin secretion to maintain normal glucose

- Reduced metabolic rate during chronic energy stress

- Altered fat storage patterns to buffer excess fuel

- Hormonal shifts that preserve energy availability

Appetite regulation changes to maintain survival

From a biological perspective, these are protective responses.

From a clinical perspective, they delay detection.

This is why individuals can show “normal” lab values while metabolic dysfunction is actively progressing beneath the surface. Compensation masks early disease.

Without understanding compensation, practitioners misinterpret early obesity and metabolic syndrome as sudden events rather than long-standing adaptive processes.

This theme is also reflected in the iThrive Academy article “The Functional Nutrition Secret to Fat Burning That Mainstream Diets Don’t Want You to Know”, which explores how metabolic regulation, not calorie math drives body composition outcomes.

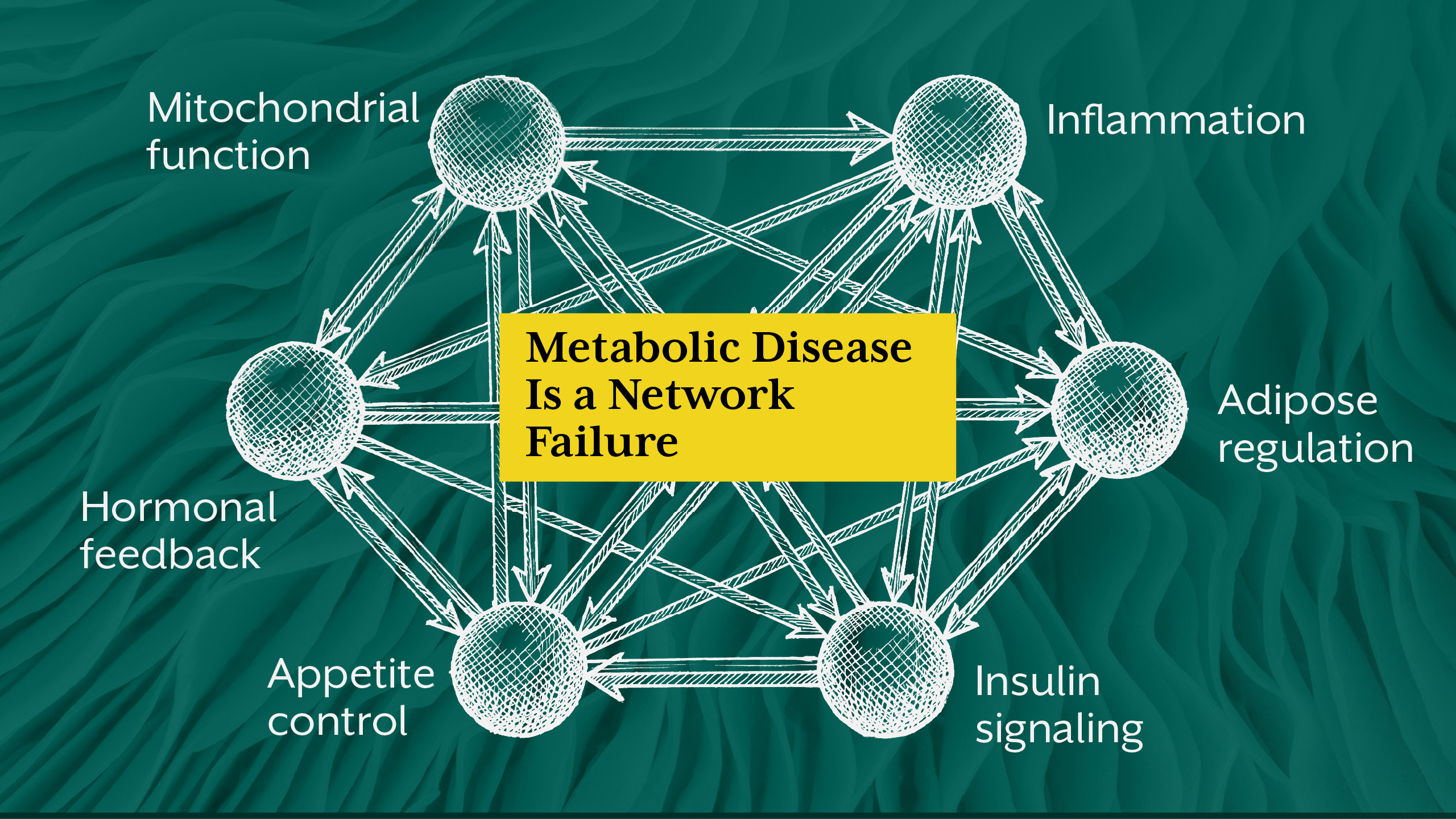

Nutrition Education Often Separates Systems That Function Together

Most curricula teach physiology in compartments:

- Carbohydrate metabolism

- Hormonal regulation

- Inflammation

- Adipose biology

- Mitochondrial function

- Gut health

Each is taught as an independent topic.

But metabolic disease emerges from system interaction, not system isolation.

For example:

Insulin resistance alters lipid handling.

Lipid overflow drives inflammation.

Inflammation disrupts mitochondrial efficiency.

Mitochondrial dysfunction impairs energy regulation.

Energy dysregulation alters appetite signaling.

This is a network failure, and not a single pathway defect.

Yet traditional nutrition training rarely teaches how metabolic systems communicate, reinforce, and destabilize one another over time.

Without systems thinking, obesity science remains fragmented.

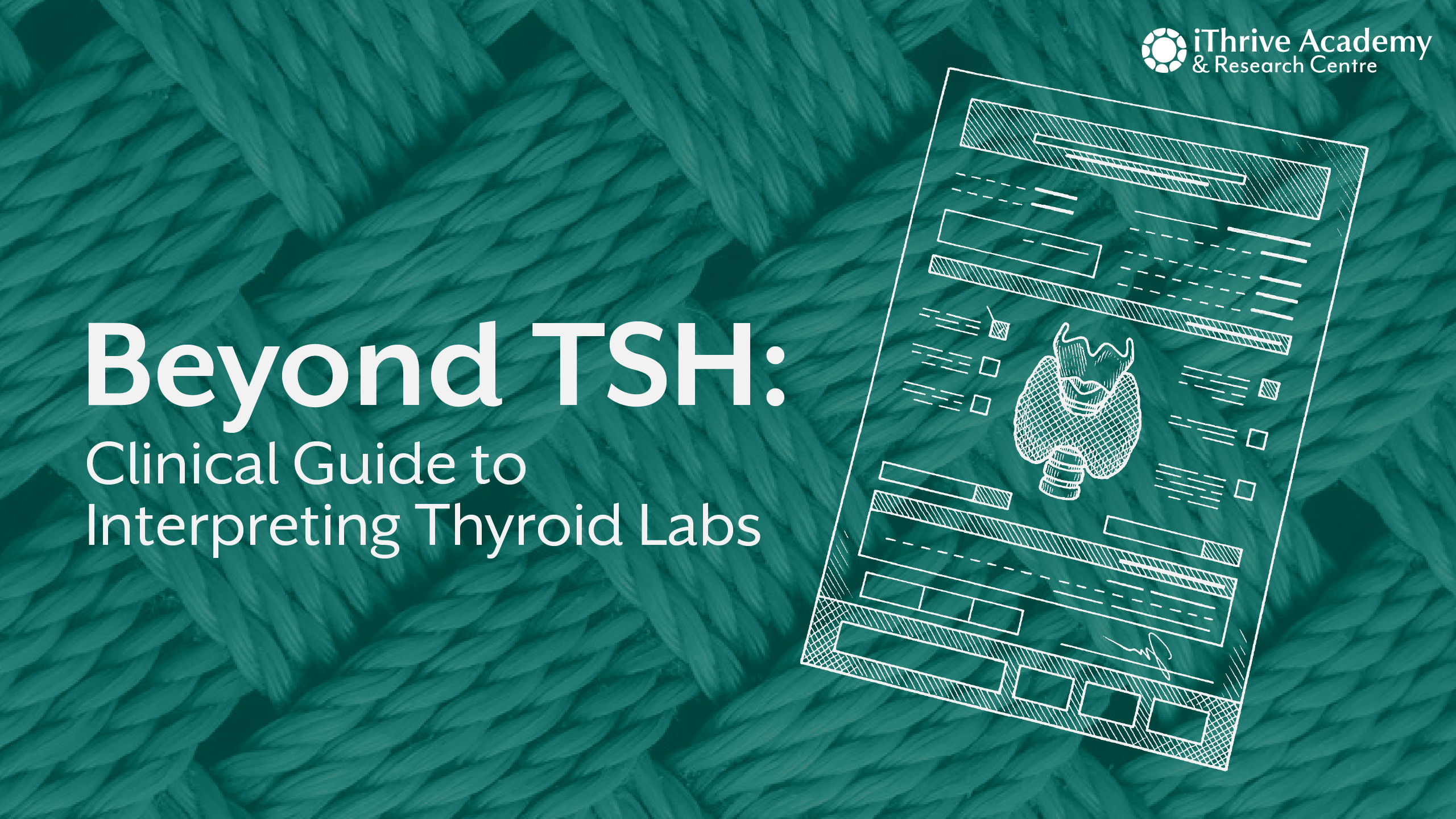

Insulin Resistance Is Often Taught Too Late in the Timeline

In many programs, insulin resistance appears primarily in the context of diabetes education.

But insulin resistance is not just a glucose disorder. It is a whole-body metabolic regulation problem involving:

- Fuel partitioning

- Cellular signaling efficiency

- Hormonal feedback loops

- Energy storage decisions

- Tissue responsiveness

By the time glucose dysregulation appears, insulin resistance has usually existed for years, and sometimes even decades.

This delayed framing leads to a reactive model of care rather than preventive metabolic regulation.

Understanding causes of type 2 diabetes requires understanding insulin resistance as an early adaptive shift, and not a late pathological event.

Metabolic Disease Is an Energy Regulation Disorder, Not Just a Weight Problem

Another major educational gap is the overemphasis on body weight as the primary marker of metabolic health.

Weight is a visible outcome, and not the regulatory mechanism itself.

Metabolic disease fundamentally reflects impaired energy handling:

- Energy storage vs release imbalance

- Reduced metabolic flexibility

- Inefficient cellular fuel use

- Altered hormonal signaling

- Chronic inflammatory activation

A person can maintain stable body weight while metabolic dysfunction progresses internally. Conversely, weight gain may represent a buffering response to energy overload.

When education equates obesity exclusively with excess fat mass, it misses the underlying regulatory disturbance.

Nutrition Training Rarely Teaches Disease Progression Architecture

In clinical reality, metabolic disease follows recognizable stages:

- Regulatory strain

- Compensation

- Reduced flexibility

- Tissue resistance

- Systemic dysfunction

- Clinical disease expression

But most education jumps directly to stage six, treatment after diagnosis.

Understanding disease architecture allows practitioners to intervene earlier, interpret symptoms differently, and identify root cause obesity rather than secondary outcomes.

This systems-level thinking aligns with broader functional nutrition frameworks explored in “Keto, Paleo, or Functional Nutrition: Which Diet Actually Wins for Long-Term Lifestyle Health?”, which emphasizes metabolic sustainability over short-term intervention models.

The Educational Focus on Intervention Over Interpretation

Most nutrition programs train learners to act before they are trained to interpret.

Diet plans. Macronutrient targets. Supplement protocols. Weight loss strategies.

But clinical understanding requires answering deeper questions:

What is the biological driver of weight gain?

What system initiated dysfunction?

Is this protective or pathological?

What is the metabolic timeline?

Without interpretation, intervention becomes standardized rather than individualized.

And metabolic disease is never standardized.

Why This Matters for Modern Practitioners and Educators

If you work clinically, or teach nutrition you have likely encountered patients whose physiology does not respond predictably to standard interventions.

Weight loss plateaus despite compliance.

Metabolic markers shift without clear explanation.

Symptoms precede measurable abnormalities.

These patterns make sense only when obesity is understood as a systems-level adaptive process rather than a simple energy imbalance.

Advanced nutrition education must therefore integrate:

- Metabolic timelines

- Compensation physiology

- Systems interaction

- Early dysfunction markers

- Long-term regulatory adaptation

This shift transforms obesity treatment from symptom management into true metabolic disease understanding.

Key Takeaway

Most nutrition courses teach obesity as an outcome to be corrected rather than a process to be understood. They emphasize energy balance but rarely explore metabolic regulation. They teach disease categories but not disease progression. They teach intervention strategies but not physiological interpretation.

True understanding of obesity and metabolic disease requires a systems perspective, the one that recognizes compensation, timeline development, network interactions, and energy regulation architecture. When practitioners learn to see obesity not as isolated fat accumulation but as a dynamic expression of metabolic adaptation, clinical reasoning deepens, prevention becomes possible, and treatment shifts from reactive management to root cause resolution.

.jpg)